Alex had returned from China with a plethora of ideas for potential improvements to the platform we were developing on, including both the hardware and software side of the robot.

Ryan and Jack began working on what would eventually become hazmat sign detection, however at this stage it was basic colour and edge detection, while Riley and I consolidated the ideas that Alex brought back from his first-hand experience in China into a new chassis.

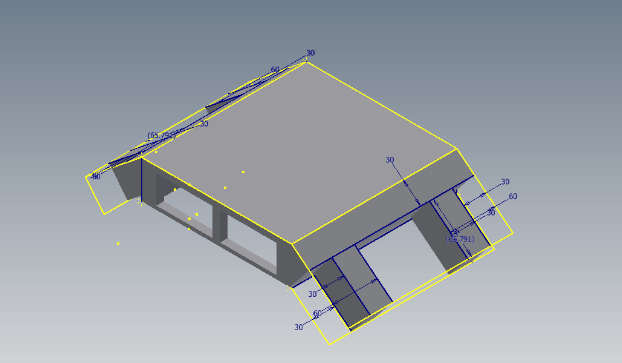

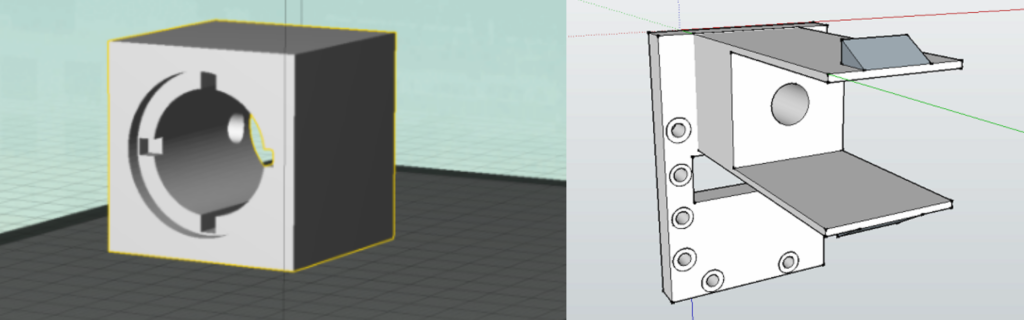

Over the next few months we experimented with the idea of creating a modular robot, with the intention being that if one of the elements broke or failed, the faulty part could be easily interchanged. Multiple iterations of locking mechanisms later, it seemed as though we couldn’t find a nice balance between size, ease of use and rigidity.

The new year came and went, and eventually we had one of the modular designs 3D printed. However glad we all were to realise the ‘fully modular’ dream, when we realised that the robot was 30 centimetres wide and wouldn’t fit within the confines of the standardised test suites provided for the competition, regrettably we scrapped this idea. With only a few weeks left before Robocup in Leipzig, Germany, I began working on a smaller, more tightly integrated version of the main chassis of the Emu Mini 2 to allow for a greater degree of manoeuvrability.

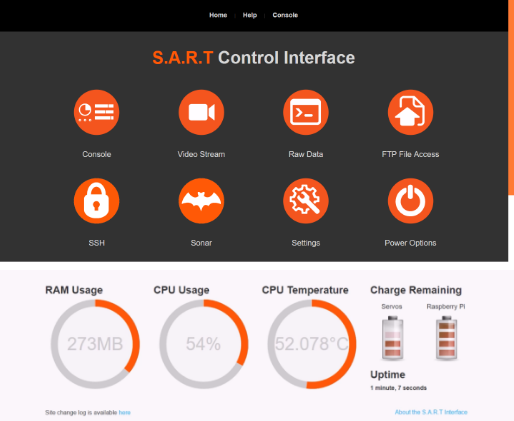

Meanwhile, in the Land Of Software, Jack had started developing a rudimentary browser based control interface. This communicated with the robot over a Wi-Fi network of Aaron’s design to utilise the control code Ryan had written to operate the robot remotely. The interface supported an SSH connection to the robot, a video stream, real-time sensor data as well as performance metric monitoring such as battery levels, CPU and memory utilisation.

The threat of exams forced all of us to redouble our studying efforts, with the slight drawback being that development slowed to a point where if it was progressing any slower, it may as well have been going backwards. After exams, there was but a week or two before Riley (our team captain and representative) needed to leave for Germany. In our frantic rush, everything that could go wrong, went wrong. There were issues with the 3D printer, issues with the woefully inadequate Raspberry Pi’s on board Wi-Fi antennae, as well as issues with the internet at school blocking the domain name resolution of the Linux package repositories we required.

Everything was in disarray, the 3D printer was constantly malfunctioning; half finished 3D printing projects were being hurled across the room in frustration accompanied with angry outbursts of expletives I hadn’t even known existed at every failed attempt to circumvent the issues with the Linux package repositories or install USB Wi-Fi adaptor drivers on Raspbian.

Then Gerard arrived. In his infinite wisdom, he suggested we fall back on the design from the previous year – essentially, integrate whatever software we had developed into the working robot we had presented Alex with to take to China.

The only problem was, the intervening year had seen this version all but destroyed, with countless holes having being drilled into the chassis to test screw alignments for mounting the internal hardware, or entire body panels being clumsily hacked away with blunt hacksaws – all in the relentless march of progress. Fishing the decrepit lump of sorry plastic out of the recycling bin, we set about mending it with liberal amounts of gaffer tape, the corpse of a plastic binder, superglue and, in a rather odd turn of events, a single piece of string.

In the fleeting light of the fading sunset, we stood back to admire our creation. It was immaculate. Something so hideous yet impossibly functional, we decided to christen it ‘Lord Elpus’, because if he couldn’t, no one could.

Despite everything that had befallen us in the lead up to the competition, we handed the robot over to Riley in the hope that at least it wouldn’t be a complete failure.

And now, a short interlude: a brief recapitulation from Riley Cockerill:

As if to rub salt in the wound only one of us was able to travel to Germany. This person couldn’t code to save his life, so any bug fixes would have to be done via Skype from halfway around the world. The trip was magnificent: with a connecting flight through Abu Dhabi to touchdown in Berlin, which, incidentally, charges for use of the public lavatory. A hop, skip and bullet train later and the Lord Elpus arrived in Leipzig.

Upon arrival, a shocking discovery was made: the single Micro SD which held ALL the software that made the Lord Elpus function in a predictable manner had been wiped from either travel damage or the x-rays at the airport. This set the tone for the next couple of days. After restoring the movement scripts and Bluetooth protocols, the Lord Elpus encountered its next major issue: the camera decided this would be a brilliant time to stop working.

In what can only be described as the single greatest instance of dumb luck: we had bought a GoPro in order to record the entirety of the event from the perspective generally found at the end of a selfie stick. Using some questionable online software and several layers of gaffer tape, the Lord Elpus acquired its new vision system, which only reinforced our reputation for solving problems with band-aid solutions. With renewed high hopes and running on very, very little sleep, the competition began.

It was a gruelling three days (which I mostly forgot due to the lack of sleep and a nasty bout of food poisoning) but, as David beat Goliath: for our plucky robot, held together only with quantities of gaffer tape one can only measure in metres and some cunning engineering had emerged, to everyone’s shocked surprise, victorious*.

It survived the drop test a total of three times followed up by twenty eight laps of the Gravel Pit and completed more of the final maze than any other robot, all the while held together only with gaffer tape and the hopes and dreams of a small robotics team from a high school in Canberra. At the end of the competition, under the gentle Croatian sunset, the valiant Lord Elpus finally stopped working – this time, it was for good. It didn’t matter, however, as it had won its place in in the halls of fame, where stories travel through the frantic, hushed whispers of those who could scarcely have believed its miraculous rise to success.

So all good then.

*I’ll just take this moment to point out that it was equal first place with King’s Legacy of Christchurch Grammar School, Perth, Western Australia.